12 iconic, new-millennial designs you should know (and why)

21st-Century Poets

We’ve been thinking a lot lately about the idea of “new classics.” Specifically, what will our current design era be remembered for 20, 50, even 100 years from now? From where we stand, thus far, the 21st-century’s greats have all been driven by a strong sense of narrative; the most moving object designs tell some sort of story, and, at their best, even change the way we relate to or interpret our surroundings.

The path that led us here was a fairly clear one. Looking back to the 1970s and ’80s—the height of postmodernism—the most influential designers (think Memphis crew, of course) championed radical works that also began alluding to the importance of a larger purpose beyond pure utility (at the same time that they shattered established ideas of style). During the ’90s, the Dutch designers—Marcel Wanders, Tord Boontje, and Droog, for example—pushed the international design conversation even farther (despite being concentrated in a particular geographic area), focusing on poetry and process in a way that allowed the narrative concept to really explode in the new millennium.

And so here we are. Today, poetic design reigns. Whether they’re embracing expert handicraft of driving material or technological innovations, for today’s most talented designers, it’s all about storytelling. Below, we’ve gathered what we consider the 12 most moving, evocative, and lyrical design objects of the 21st century to date for your edification and enjoyment.

1) Smoke by Maarten Baas (2002)

Dutch designer Maarten Baas's debut project, Smoke—developed for his 2002 graduation from Design Academy Eindhoven and expanded over the next few years with Moooi and then Moss—set the design world literally on fire. The iconic collection includes various classic and vintage design pieces, from Rietveld’s Zig Zag Chair and Sottsass’s Carlton Cabinet to a vintage high chair, all charred with a flamethrower and then preserved with an epoxy resin.

2) Panda Banquete Chair by Fernando & Humberto Campana (2005)

Since the 1990s, the Campana brothers have built an international reputation for their ingenious re-use and re-invention of commonplace odds-and-end, such as rope, aluminum wire, plastic tubing, fabric remnants, and stuffed animals. The Panda Banquete Chair is a perfect example of their signature style, repurposing the humble stuffed animal to create a poetic, vibrant chair with a definitively Brazilian energy. The stuffed pandas are hand-sewn onto canvas stretched over a stainless steel structure.

3) Bathboat by Wieki Somers Studio (2005)

Inspired by custom and ritual, Studio Wieki Somers has built a career on the concept of magical realism, adding a sense of wonder to everyday objects. Cofounders Wieki Somers and Dylan van den Berg are champions of fantasy; in their capable hands, a common coat rack, for example, becomes a merry-go-round (Merry-go-round Coat Rack, 2009) and a bathtub becomes a whimsical fishing boat, ready to take to the sea. According to the Rotterdam-based designers, "It started with watching a fisherman floating on a lake one morning. Peaceful, timeless, somehow mysterious and deeply banal at the same time."

The lacquered oak and red cedar Bathboat is part of the permanent collection at the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam. It is available through Galerie Kreo in Paris.

4) Honeycomb Vase by Tomáš Gabzdil Libertíny (2005)

The beeswax Honeycomb project was conceived in 2005 while Libertíny was still a student. After shadowing beekeepers for four months, the Slovakian-born, Rotterdam-based designer "invited new colonies of bees to participate" in his design. For each, a swarm of bees creates a hive around a pre-made, vase-shaped beeswax scaffold structure (which the designer refers to as a “slow prototyping” process, in direct contrast to the era’s rapid manufacturing technologies). Results vary depending on season, geography, colony size, and weather. In 2008, one of the vases was acquired by MoMA after being featured in its landmark Design and the Elastic Mind exhibition. The project has since extended to other “made by bees” concepts, and Libertíny continues to explore the relationship between nature, science, and technology in his work.

5) Bone Furniture by Joris Laarman (2006)

Joris Laarman’s digitally fabricated Bone Furniture also found inspiration in the natural world—at the same time that it espoused the poetic possibilities of new technologies. Developed from an algorithm that replicates the functionality and complexity of the human bone, the series' debut project, the 2006 Bone Chair, was cast in a single piece using a custom 3D printed ceramic mold. (Other Bone pieces have since followed in a variety of materials.) As Laarman has noted: “Ever since industrialization took over mainstream design we have wanted to make objects inspired by nature . . . Our digital age makes it possible to not just use nature as a stylistic reference, but to actually use the underlying principles to generate shapes like an evolutionary process.”

Notably, Laarman continues to work at the crossroads of technology and design; his recently announced MX3D is slated to 3D-print a steel bridge over an Amsterdam canal with that can “draw.”

6) Cherry Blossom Canopy by David Wiseman (2006)

For the 2006 National Design Triennial at the Cooper Hewitt, David Wiseman covered the Carnegie Mansion’s ceiling with a beguiling web of cast plaster branches and fired porcelain blossoms. The installation was a landmark moment for the L.A. designer, bringing his work—a celebration of both nature and decorative arts—to a sizable audience.

He’s since gone on to do numerous nature-inspired, site-specific installations for a variety of private and public clients. Just this past month, Wiseman took over NYC gallery R & Company with a gorgeous solo show entitled Wilderness and Ornament (on view through June 25th).

7) Pewter Stool by Max Lamb (2007)

While Max Lamb’s Pewter Stool is beautiful, it’s the unexpected process behind it that makes it truly poetic. The innovative British designer cast his stool in sand on a Cornish beach (a favorite spot from his childhood), pouring molten pewter into a geometrically patterned mold sculpted directly in the sand by hand. Once the pewter cooled, Lamb dug away the sand to reveal the finished stool. Given that every mold can be used only once—and the volatility of the seaside setting—Lamb’s stools are inevitably each unique.

8) Sketch Furniture by Front Design (2007)

Swedish design studio Front wondered: What if we could make a physical object out of a simple sketch? The design quartet—Anna Lindgren, Katja Sävström, Sofia Lagerkvist, and Charlotte von der Lancken—figured out a way to do just that, developing a technique wherein pen strokes drawn mid-air are recorded using motion capture, then converted into 3D digital files. Thanks to rapid prototyping, the sketches then materialize as hard plastic pieces that they coat in white lacquer. From doodle to reality, just like that.

9) 100 Chairs by Martino Gamper (2007)

For his breakout project, Italian-born, London-based Martino Gamper spent two years collecting chairs from London alleyways and friends’ homes. Then, over the course of 100 days, he set about taking them apart and reassembling them—one each day—into poetic, often very quirky forms.

As Gamper has noted, “I wanted to question the idea of there being an innate superiority in the one-off, and used this hybrid technique to demonstrate the difficulty of any one design being objectively judged The Best. I also hope my chairs illustrate—and celebrate—the geographical, historical, and human resonance of design: what can they tell us about their place of origin or their previous sociological context and even their previous owners? For me, the stories behind the chairs are as important as their style or even their function.”

100 Chairs in 100 Days debuted in London in 2007, and has toured the globe ever since. In fact, its latest iteration just opened at Japan’s Marugame Genichiro-Inokuma Museum of Contemporary Art (MIMOCA), and runs through September 23, 2015.

10) Cabbage Chair by Nendo (2008)

For Oki Sato, the man behind the Japanese studio Nendo, design is an opportunity to transform everyday objects and spaces into what he calls "aha" or "!" moments. The Cabbage Chair captures this ethos perfectly. Commissioned by fashion designer Issey Miyake, Nendo's Cabbage Chair transformed a roll of pleated paper (a discarded byproduct of Miyake’s Pleats Please fashion line) into an unexpected furniture design. As one peels away the upright roll’s outer layers, like an onion, an oh-so-charming chair is revealed.

11) Stellar by Tokujin Yoshioka (2010)

Japanese designer Tokujin Yoshioka is known for his stunning, emotionally evocative installations and objects. Great design, he has said, “stirs the human heart and transcends language, ethnicity, and national borders. I believe that emotion itself is what completes design.” Yoshioka's Stellar chandelier for the 2010 Swarovski Crystal Palace at the Milan Furniture Fair certainly met that criteria. The “living crystal” chandelier—Yoshioka's attempt at creating an artificial star—was actually grown in a tank filled with a mineral solution. Yoshioka placed a block of soft polyester fiber within an aquarium, and the natural crystals grew gradually over the course of a month. According to Yoshioka, the ethereal, unpredictable nature of the design is at the heart of its beauty, one “born of coincidence during the formation process of natural crystals.”

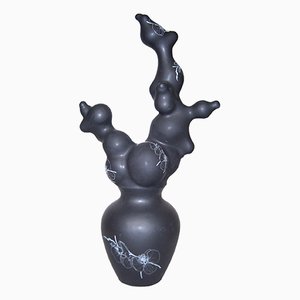

12) Botanica by Formafantasma (2011)

In 2011, the Plart Foundation—an institute dedicated to preserving plastic works of art and design—commissioned Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin (the design duo behind Formafantasma) to launch a retrospective study of the history of plastic. The resulting collection, called Botanica, is the designers’ homage to the material. Designed as if the oil-based era we now live in never took place, the Italian-born, Amsterdam-based designers experimented with 18th- and 19th-century techniques to create natural polymers extracted from plant and animal sources, which were then combined with traditional materials like wood, metal, and ceramics for a series of vases, bowls, lighting, and furniture in shapes and colors inspired by nature. The studio notes that as the world moves “towards a new post-oil era, the pre-oil era is starting to be globally re-discovered in search for alternatives.”

Originally presented at Spazio Rossana Orlandi in Milan, Botanica is now part of the permanent collections of institutions such as the MoMA and Art Institute of Chicago. Thanks to Formafantasma’s love of craftsmanship, the studio continues to explore historical techniques and consistently experiments with unusual materials, from bread and sea sponges to salmon skin and fur to create truly lyrical designs.

More to Love

Alphabet Water Pitcher by Formafantasma

Clay Bench in Green by Maarten Baas

Alphabet Water Glass by Formafantasma

Alphabet Water Glass by Formafantasma

Green No 03 Assembled Stool by Studio Wieki Somers

Green No 4 Cardboard Tape Box by Wieki Somers

Elevated Green No 1 Extended Stool by Wieki Somers

Green 3-Legged No 2 Tripod Stool by Wieki Somers

Chinese Stools – Made in China, Copied by the Dutch 2007, Green from Studio Wieki Somers, Set of 5

Blue Diptych by Tomáš Libertíny for Studio Libertiny, 2017, Set of 2

Weldgrown Wall Piece By Tomas Libertiny For Studio Libertiny, 2017

Weldgrown Wall Piece by Tomáš Libertíny, 2017

Light Pink Mattress Stone Bottle from Studio Wieki Somers, 2002

High Tea Pot from Studio Wieki Somers, 2003

Black Blossoms Vase by Studio Wieki Somers, 2005

White Blossoms Vase Without Holes from Studio Wieki Somers, 2005

Red No 01 Extended Stool by Studio Wieki Somers

Red No 04 Cardboard Tape Box by Wieki Somers

Green 4-Legged No 05 Carpenter Stool by Studio Wieki Somers

Red No 03 Assembled Stool by Studio Wieki Somers

Red 3-Legged No 2 Tripod Stool by Studio Wieki Somers

Chinese Stools – Made in China, Copied by the Dutch 2007, Red from Studio Wieki Somers, Set of 5

Light Green Mattress Stone Bottle from Studio Wieki Somers, 2002

Clay Low Seater by Maarten Baas

Sketch Furniture by Front; image courtesy of the designers.

Sketch Furniture by Front; image courtesy of the designers.

Sketch Furniture by Front; image courtesy of the designers.

Sketch Furniture by Front; image courtesy of the designers.

Pieces from Martino Gamper's 100 Chairs collection; photo © Åbäke and Martino Gamper.

Pieces from Martino Gamper's 100 Chairs collection; photo © Åbäke and Martino Gamper.

The Cabbage Chair by Nendo. Photos © Masayuki Hayashi; courtesy of Nendo.

The Cabbage Chair by Nendo. Photos © Masayuki Hayashi; courtesy of Nendo.

Stellar by Tokujin Yoshioka for Swarovski Crystal Palace at Salone del Mobile 2010. Photo courtesy of Tokujin Yoshioka.

Stellar by Tokujin Yoshioka for Swarovski Crystal Palace at Salone del Mobile 2010. Photo courtesy of Tokujin Yoshioka.

Stellar by Tokujin Yoshioka for Swarovski Crystal Palace at Salone del Mobile 2010. Photo courtesy of Tokujin Yoshioka.

Stellar by Tokujin Yoshioka for Swarovski Crystal Palace at Salone del Mobile 2010. Photo courtesy of Tokujin Yoshioka.

Botanica by Studio Formafantasma, commissioned by the Plart Foundation. Photo by Luisa Zanzani; courtesy of Formafantasma.

Botanica by Studio Formafantasma, commissioned by the Plart Foundation. Photo by Luisa Zanzani; courtesy of Formafantasma.

Botanica by Studio Formafantasma, commissioned by the Plart Foundation. Photo by Luisa Zanzani; courtesy of Formafantasma.

Botanica by Studio Formafantasma, commissioned by the Plart Foundation. Photo by Luisa Zanzani; courtesy of Formafantasma.