Designers tackle the future of plastics

The Start of Something Good

Take a look around you. How many things in your immediate surroundings contain plastic? Quite a few, right? The more you start looking, the more you realize that even things that don’t appear on the surface to be made of plastic, in fact, involve plastic fittings, finishes, inserts, or wrappers. Now consider the billions of other people on earth who also have plastic within arm’s reach right now. And here’s a wild thought: nearly all of the plastics that have been manufactured over the last century still exist somewhere on the planet.

Recently, we traced the history of how plastic, one of the most versatile design mediums ever conceived, became ubiquitous in our everyday environment. The story covered the transformation of plastic from a necessary wartime innovation to a dream-material for psychedelic ’60s designers and on to the high-performance material of the ’80s, ’90s, and beyond. Chemical advancements in the stabilization of synthetics have made plastics increasingly durable and resistant to natural degradation. It’s painfully ironic, then, that plastic became synonymous with cheap, throwaway products. Even after tossing it in the garbage, plastic takes centuries to breakdown. Burning it releases toxic chemicals, and recycling is often difficult and resource-intensive. Sixty years ago, plastic seemed to hold the cure for every design ill that plagued us; today plastic is the plague.

Thankfully, a growing segment of the design community is exploring a new wave of alternatives to oil-based plastics—collectively called bioplastics. For the uninitiated, these materials are made from natural resources, such as corn or potato starch, sugarcane, cellulose from trees and straw, microbiota, or even insects. They’re generally engineered to biodegrade at a much faster rate than conventional plastics, and many compost at the end of their useful life, aided by fungi, bacteria, and natural enzymes. There is still a long way to go—today’s problems of scalability, durability, and flexibility of application are similar to those that faced chemists during the early development of oil-based plastics—but the bioplastic field is intensifying, not only in size but also ambition and successes.

Attua Aparicio and Oscar Wanless, the designers behind London-based Silo Studio —a standout in the arena with a penchant for incorporating industrial materials into a craft-based approach—explain that we’re at a precarious moment of development, “where bioplastics and more sustainable materials are designed to replace plastics—and are measured and judged against [their] ability to work exactly as [their] predecessor.” This is a crucial point, because while there are a few products already on the mass market—like the attractive, Eames Chair-esque Kuskoa Bi chair from Jean Louis Iratzoki and Alki, purported to be the first bioplastic chair in production—this range of materials is still very much in its adolescence. Nonetheless, dismissing bioplastics because they do not currently and immediately eliminate the demand for oil-based plastics is shortsighted. As the Silo Studio team says, “The way forward is to look at the newly developed materials and, after experimentation and understanding their individual properties, start designing with them now.”

Experimentation is definitely the backbone of the bioplastics game. Silo Studio is working with materials that might be considered stepping-stones between traditional plastics and bioplastics. Recently they have begun forays into using the UPM plastic composite ForMi, which incorporates up to 50% renewable material, beginning with the PPPPP range of brilliantly colored, painterly bowls and trays. With a tactile quality somewhere between wood and plastic, and, as the designers explain, a “good proportion of the material” being derived from renewable paper pulp, “it also greatly reduces the CO2 use in its production.”

Here’s another example that recently caught our imagination: the Spud Coat is a handy, waterproof poncho made from completely compostable bioplastic that also contains a small clay ball and seeds—so when you’re done wearing it you can plant it and wait for a tomato plant to grow. Now this particular item may not be the height of design chic, but imagine if your summer outdoor furniture could compost over the winter only to sprout into a new flower or vegetable patch the following year! Or consider the Bite Me lamp from quirky, New York-based designer Victor Vetterlein; made from an algae base, the lamp—minus LED lighting strip—is completely edible and comes in a range of flavors.

The trend is definitely towards a much closer, more direct link between design and nature. Philippe Starck, one of the design names most closely linked with plastics, has been conspicuously ambivalent about both recycled and bioplastic alternatives to traditional plastic, rejecting both in a 2008 interview with Wired, but perhaps even this stalwart of the plastic age has been seduced by the possibilities of new, alternative materials. In 2011, he teamed up with Eugeni Quitllet to debut the Zartan Chair range with Magi; the production house describes the material used as “recycled polypropylene with wood fiber added,” but the material is also known as “liquid wood.” The technique was probably first developed by TECNARO, a producer of thermoplastics from renewable resources, and involves extracting the natural polymer lignin from waste created by the pulp industry and combining it with natural fibers like flax or hemp. According to the company, with the help of a few other natural additives, the fiber composite can be processed at high temperatures and used in conventional plastics processing machines, just like a synthetic thermoplastic material.

German designer Werner Aisslinger also experiments with natural fibers as plastic substitutes. In 2012, he teamed up with Moroso to release the Hemp Chair, an echo of the iconic Panton Chair that, according to manufacturer, is the “worldwide first natural fiber monochair". The material was developed with the German chemicals giant BASF and involves molding the hemp at high temperatures with a special sustainable glue to create a new composite material that is both light and sturdy. Luxury British car company Lotus is reportedly also investigating a hybrid hemp composite to make the body panels of cars. According to George Elvin, author of the book Post-Petroleum Design, Lotus started using it for interior fabrics before expanding their research to include external applications.

Proving that it doesn’t have to be the biggest players who lead the way, 25-year-old Dutch designer Aagje Hoekstra is the inventor of a remarkable bioplastic made from pressed insect shells; a material which she has dubbed Coleoptera. Mealworms are commonly bred for the animal food industry, but the mealworm beetles that produce the larvae are considered waste once they have laid their eggs—it is with this raw material that Hoekstra chose to work. And considering that there are more insects in one square kilometer of land than humans on the entire planet, she may be on to one of the most renewable sources out there. Chitin (which is, after cellulose, the most common polymer on earth) is found in the beetles’ armor. Once the mealworm beetle shells have been separated, the chitin can be chemically purified and then transformed into chitosan—a variation of the same polymer that bonds more readily. Hoekstra then presses the substance to create sheets of her “insect plastic.” That is the science-y way of explaining it. Visually, the material looks something like a cross between spun gold and stained glass. Hoekstra, who has shown at Salone del Mobile in Milan and picked up several awards on the Dutch design scene, has so far used Coleoptera to craft gorgeous, organic-looking jewelry and glowing light objects.

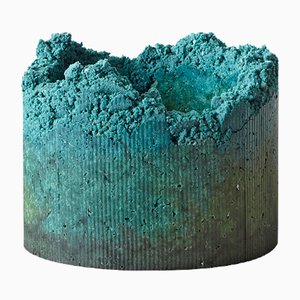

Berlin-based studio Krupka-Stieghan is also working on sustainable solutions to industrial waste problems. In fact, award-winning designers and cofounders Katrin Krupka and Philipp Stieghan have successfully made sustainability the key to their aesthetic. The designers saw value in industrial cotton waste (all the off-cuts, threads, cotton dust, and even fluff from industrial tumblers) and worked with manufacturers, research institutes, and chemists to create a range of bioplastics utilizing cotton production by-products that would otherwise be burned. The Recreate Textiles line of hand-formed bowls and vessels turn the unique texture and pattern of the cotton fibers into a stunning design feature. Cotton Marble is another exciting project from the young German designers: the current state of development only allows for decorative use—and the subtle, marbled sheets pressed from industrial cotton waste using bioplastic are gorgeous and invitingly tactile—but experimentation continues and Krupka-Stieghan hope to further expand the capabilities and applications for their material.

With so much diversification of materials and approaches underway, there is a sense of real hope that the disposable consumerism that evolved in parallel with oil-based plastics can transformed, gradually phased out in favor of more ecological alternatives. Peter Marigold, English design star and former student of Ron Arad, is somewhat of an evangelist for Polymorph low-temperature thermoplastic, a starch-based bioplastic that is food safe and biodegrades within about six weeks. The designer has led several workshops, supported by Vitra Design Museum and the Pompidou Center, aimed at opening up this material to the design and maker community. As Marigold explains, “I could see the enormous potential in the material, so I was trying to figure out why people don’t have it in their kitchen drawer.”

Marigold's experience during the workshops led him to conclude that the catch for most people was the granulated form of his beloved thermoplastic—it can be messy to press and form into sheets. This simple realization gave birth to an idea: the FORMcard; handily sized, colored sheets of bioplastic that can be made malleable just by dipping them in a cup of hot water. Not only can FORMcards be shaped into any form imaginable (a custom phone-holder or ad hoc tool, perhaps) but, more importantly, the warmed thermoplastic bonds easily with other oil-based plastics and can therefore be used to repair or customize objects that would otherwise end up in landfill. Marigold believes in the creativity of people, not just their ability to consume. “We’ve been trained to think that objects are things that we can only receive rather than make or change. FORMcard is about putting making and mending back into the hands of the consumer.” Think of it as an exponentially more effective means of repairing an object than those times you tried it with sticky tape or super glue.

In this same spirit of reuse and waste usage, which accepts that—for now at least—conventional plastics are still a massive part of industry and production, 2010 Design Academy Eindhoven graduate Ruben Thier created a series of eye-catching, sculptural benches and stools from industrial plastic waste for his final graduation project. For Organic Factory, Thier placed containers beneath factory machinery to catch plastic waste and overproduction that would otherwise drip onto the floor. Once cut and fitted with minimalist, angled chrome legs, the plastic waste is transformed into a family of astoundingly decorative (due to the range of colors, marbling of material, and undulations of the liquid material that are captured in the solid form), absolutely au courant seating objects.

It is clear that the technology is not yet sufficiently advanced to a point where oil-based plastics can realistically become a thing of the past, and there is also considerable resistance from industry that needs to be overcome. What is also clear, however, is that a new industry is beginning to reach maturity, one imbued with an adventurous sense of optimism, that is working towards alternatives to our current addiction to plastic. Bioplastics will certainly improve in their stability, breadth of application, and scalability over the coming decades. Technical and material innovation alone, however, will not suffice: even some bioplastics release harmful greenhouse gases like methane, or may leave a toxic residue, while biodegrading. Scaling up production of corn-based bioplastics could mean more deforestation. And the transitional phase during which both recyclable oil-based plastics and bioplastics are on the market is likely to lead to even greater difficulties in recycling existing materials. To wit, just one PLA (a type of common bioplastic) item thrown into a PET (one of the most common traditional plastics used in packaging) recycling bin can ruin the entire collection. What is needed is a multipronged approach—one that includes the multiple approaches employed by the designers in this story—and numerous others, of course—of recycling and re-using plastic and other waste products from existing industries; developing, experimenting with, and promulgating plastic alternatives; and rousing the broader public from its throw-away mentality while encouraging people to make, repair, and re-use.

Perhaps these seemingly opposing, yet complementary, viewpoints can best be described by two quotes: one from the old guard and one from the vanguard. Philippe Starck put it bluntly when he said, “The best ecological strategy is to make products of a very high creative quality, so you can keep them for three generations. I prefer to make a very good chair in the best polycarbonate than make any shit in wood that will be in the trash one year later.” Silo Studio, on the other hand, embrace the future when they say, simply, “With change there will be opportunity—and this should be used creatively.”

-

Text by

-

Gretta Louw

A South-African born Australian currently based in Germany, Gretta is a globetrotting multi-disciplinary artist and language lover. She holds a degree in Psychology, and has seriously avant garde leanings.

-

More to Love

Small Well Proven Stool by Marjan van Aubel & James Shaw for Transnatural Label

Structural Skin Table Lamp Nº02 by Jorge Penadés, 2017

Structural Skin Table Lamp Nº04 by Jorge Penadés

Chimbarongo 18-Light PET Lamp by Alvaro Catalán de Ocón for ACdO/

Eperara Siapidara 12-Light PET Lamp by Alvaro Catalán de Ocón

Medium Well Proven Stool by Marjan van Aubel & James Shaw for Transnatural Label

Industrial Craft Table 03 by Charlotte Kidger

Industrial Craft Table 02 by Charlotte Kidger

Industrial Craft Vessel 02 by Charlotte Kidger

Honeycomb Black Pillow by R & U Atelier

Honeycomb White Pillow by R & U Atelier

Natural Furry Range Pillow by R & U Atelier

Fringe Cotton Pillow by R & U Atelier

Fringe Furry Pillow by R & U Atelier

Structural Skin Table Lamp Nº03 by Jorge Penadés, 2017

Roll Lamp (Large) by Sébastien Cordoleani

Gesso Lamp Ochre & White by Jonas Edvard

Roll Lamp (Small) by Sébastien Cordoleani

PET Lamp Chandelier by Alvaro Catalán de Ocón

Yellow & Beige Cotton Bowl by Krupka-Stieghan

Black & Yellow Cotton Bowl by Krupka-Stieghan

Black & Beige Cotton Bowl by Krupka-Stieghan

Large Beige Cotton Bowl by Krupka-Stieghan

Beige & Yellow Cotton Bowl by Krupka-Stieghan

Gesso Lamp in White by Jonas Edvard

Gesso Lamp in Anthracite by Jonas Edvard

Gesso Lamp in Berlin Blue by Jonas Edvard

Gesso Lamp in Anthracite & White by Jonas Edvard