Brutalist design is all about fearless and frank craftsmanship

Qu'est-ce que c'est Brutalism?

-

Svend Aage Holm Sørensen Wall Lamp (1960s)

Photo © Van Ons

-

Adrian Pearsall Dining Table for Craft Associates (1970s)

Photo © Mid Century Online

-

Belgium Brutalist Sideboard (1970s)

Photo © Goldwood

-

Sergio and Giorgio Saporiti Dining Table (1970s)

Photo @ city-furniture

-

Georges Mathias Coffee Table (1970s)

Photo @ city-furniture

-

German Unpolished Brass Sconce (1960s)

Photo @ city-furniture

-

Paul Kingma Coffee Table (1986)

Photo @ city-furniture

-

Belgium Brutalist Sideboard (1970s)

Photo @ city-furniture

-

Scheruich Lava-Glazed Vase (1970s)

Photo @ city-furniture

-

Spanish Bar Stools (1970s)

Photo © Dusty Deco

-

Adrian Pearsall Dining Chairs for Craft Associates (1970s)

Photo © Mid Century Online

-

Cream Stoneware Vase by Gunnar Nylund for Rörstrand (1950s)

Photo © tack.

-

Anonymous Ceramic & Brass Pendant

Photo @ city-furniture

-

Belgium Brutalist Sideboard (1970s)

Photo @ city-furniture

-

Anonymous Wood Sideboard

Photo @ city-furniture

Spurred by the opening of Met Breuer last year, profiles on Brutalist architecture have overrun media for months. With all this talk about Brutalism, it’s surprising that there hasn’t been more coverage of the many design objects that bear the same label—especially since the market for this sprawling style has been skyrocketing.

Like a flooded river that’s broken its banks, the Brutalist tag spread far beyond its architectural foundations; first into large, monumental furniture that bore a striking physical resemblance to the buildings, and then into an array of decorative arts objects, from the coarse and punk rock to the highly ornate and glam. With little consensus around a strict definition for Brutalism in design, it seems most people are comfortable with taking the “I know it when I see it” approach.

Burrowing into the history, however, it’s clear that Paul Evans is the key to unlocking the Brutalist design puzzle. Trained in metallurgy before studying at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, Evans practiced at the intersection of art, craft, and design, working predominantly in metal. He became a major player in the American craft movement of the 1960s and ’70s, which coincided with the proliferation of Brutalist architecture.

Though Evans’s purely artistic aims never overlapped with the more practical intent of Brutalist architects, his distinctive, super welded cabinets and wall sculptures set the tone for all that would be called Brutalist in design ever after. It’s ironic, then, that gallerist and design scholar Todd Merrill tells us, “Brutalist is not a definition that Paul Evans liked or wanted used to describe his work, even though he could not escape it. Yet from his earliest output, the term was foisted on him by critics and patrons alike.”

Evans’s ongoing series of sculpted steel cabinets from the ’60s and ’70s became emblematic of Brutalist interior design and furnishings, thanks, at least in part, to their repeating, sharply angled geometry and often raw, unpolished edges. Looking at simpler early pieces, or even the glossier, faceted credenzas of the ’70s, the similarities with Brutalist architecture, in form and expression, is obvious. Interestingly, Merrill is not so sure that the influence was in the direction that one might imagine, adding “to the eye of any amateur aficionado who is aware of Paul Evans, the influence of his work can be seen in the architecture around us in New York City.”

No matter who influenced whom, key differences remain between Evans’s furniture and the Brutalist buildings of his time. Evans meant his work to be seen as collectible craft-art; its appreciation lay in its hand-wrought skill and intuition-driven composition; and its patrons displayed the work within luxurious interiors, especially as the 1970s wore on. Since 2005, vintage pieces by Evans have enjoyed high prices at auction and galleries. Just last year, one of Evans’s cabinets from 1970 sold at Wright for $293,000.

But Evans wasn’t the only furniture maker producing handcrafted, sculptural objects in metal in those years. His contemporaries who shared a penchant for rough-hewn structures and layered, patchworks of raw materials include Americans Adrian Pearsall and Marc Weinstein, for instance, who were also called Brutalist. From there, like a benevolent virus, the moniker began to infect just about any object produced in metal around the 1970s, including pieces that favored botanical forms over the geometric. Not stopping there, it eventually stuck to pieces made in wood and patterned with repeating shapes, as well as ceramics with highly textured surfaces and, coming full circle, anything composed of raw concrete.

Amsterdam-based vintage dealers Ambra and Rik van Ons define Brutalism in design as “a bit like the postwar architecture—angled, blocky, geometric, graphic, and raw—riffing off of the architecture but without recreating it.” They believe that the difficulty in defining Brutalist design arises from its many intersections with modernist and even industrial-style objects, which share a lot of the adjectives on the van Ons’s list. The duo goes on: “Where there were already many refining details omitted in modernist design, Brutalism continued. Materials are even rougher and coarser, lacking the polish of modernist pieces.” Brutalism could be seen to be the unruly offspring of modernist aesthetics and industrial materials.

Joop Schot of Artbrokerdesignin the Netherlands, however, prefers to draw a sharper distinction between Brutalist objects and industrial objects, even though they all employ less polished materials. “Industrial design tends to be mass produced while Brutalist pieces are usually limited-edition pieces that lean more towards design-art,” he explains. For him, authentic industrial pieces were created with functionality in mind; they are utilitarian and have become more beautiful over time by the patina of use. Brutalist pieces are—and this is a subtle but key difference—made not only for utility but to express a notion of beauty beyond pure function.

Lenz Vermeulen from City Furniture in Antwerp has watched the label gain momentum over the last decade, saying he first started selling furniture that would now be referred to as Brutalist in 2006, although it didn’t bear that label back then. “At the time, I didn’t look at, for instance, wood sideboards with graphically patterned doors as ‘Brutalist’ furniture,” remembers Vermeulen. And he’s still not sure there really is such a thing as Brutalist furniture. “I believe it’s a style people refer to because it makes us think about the architectural style. But this rleationship is very loose.” The amount of decorative detail found on a lot of pieces that are now labeled Brutalist can feel quite far afield from, say, the warehouse-inspired architecture of Brutalist pioneers Alison and Peter Smithson.

“The distance between the original Brutalist buildings and the design objects now called Brutalist can be seen very well in the brass light fixtures of Danish designer Svend Aage Holm Sørensen, who used reiterating forms—diamond shapes or ragged leaves—that were processed in a very coarse manner,” says Ambra van Ons. It is the “wonderful contrast” between the flamboyant forms and the unfinished state of the materials that creates the allure. Similar effects can be found in the palm tree-shaped brass lamps produced by Maison Jansen and other French ateliers in the 1970s. And in the end, these distinctive objects lend themselves well to today’s taste for eclecticism. Ambra van Ons gushes about Brutalist interiors even as she mainly specializes in modernist pieces from the Netherlands and Scandinavia. “But how cool is a Memphis vase on a Brutalist cabinet beside a modernist armchair?” she enthuses.

This is perhaps the crux of Brutalism’s rise in popularity in the last decade. It embodies a more disruptive, more individualistic and authentic take on interior design. Schot points to Ron Arad’s iconic DIY Rover Chair (1981) as another example of what Brutalism is all about. Decades of saccharine sweet marketing and overly controlled visual culture have instilled a craving for something with a hint of wildness. In that sense, the rise of Brutalism goes hand in hand with the newly awakened interest in contemporary takes on traditional crafts. But where artisanal works tend to feel warm and even comforting, Brutalism always has that uneasy sense of the unfamiliar, even a hint of sci-fi. Despite the wide variance among objects deemed Brutalist, those attracted to this of-the-moment style all share a desire to do things their own way; along the way embracing a desire for freedom, fearlessness, and craftsmanship.

* To learn more about the architectural foundations of Brutalist design, check out Part I of this story, The Bold & the Beautiful.

-

Text by

-

Wava Carpenter

After studying Design History, Wava has worn many hats in support of design culture: teaching design studies, curating exhibitions, overseeing commissions, organizing talks, writing articles—all of which informs her work now as Pamono’s Editor-in-Chief.

-

-

Text by

-

Gretta Louw

A South-African born Australian currently based in Germany, Gretta is a globetrotting multi-disciplinary artist and language lover. She holds a degree in Psychology, and has seriously avant garde leanings.

-

More to Love

Brutalist Coffee Table by Paul Kingma, 1990

Mid-Century Brutalist Iron Candleholder

Brutalist Danish Brass Pendant Lamp by Svend Aage Holm Sorensen, 1960s

Mid-Century Brutalist Pendant Lamp by Nanny Still, 1960s

Scandinavian Brass Wall Light by Svend Aage for Holm-Sorensen, 1960s

Brutalist Wall Lamp by Sven Aage Holm Sørensen for Holm Sørensen & Co, 1980s

Brutalist Wall Lamp by Sven Aage Holm Sørensen, Holm Sørensen and Pedersen, 1960s

Vases by Marcello Fantoni , 1970s, Set of 2

Midcentury Brutalist Copper Candleholder

Brutalist Massive Oak Wood Shelving, 1950s

Brutalist Brass Wall Light by Sven Aage Holm Sørensen, 1950s

Brutalist Brass Chandelier by Bertil Brisborg, 1950s

Brutalist Oak Bar Cabinet

Brutalist Danish Brass Wall Lamp by Svend Aage Holm Sorensen, 1960s

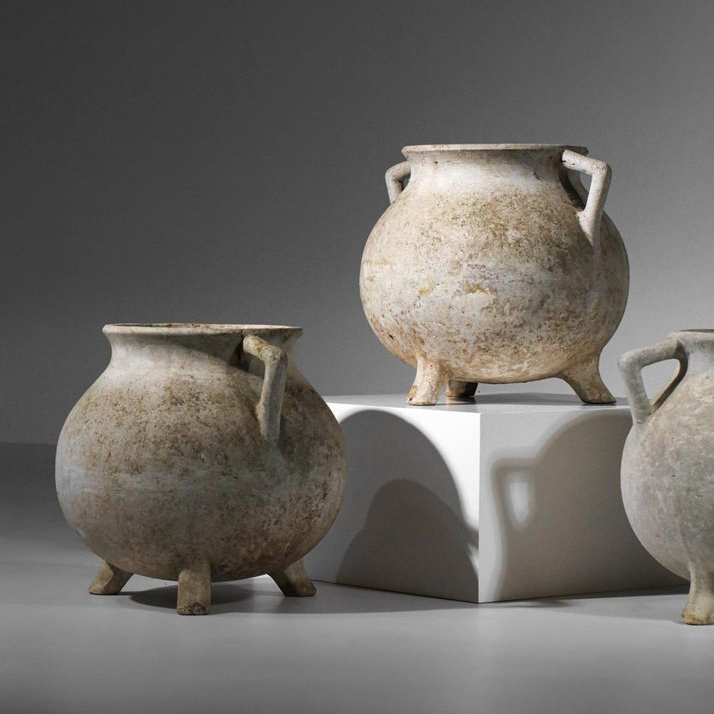

Marmite Pflanzgefäße von Willy Ghul, 1960er

Photo © Danke Galerie

Marmite Pflanzgefäße von Willy Ghul, 1960er

Photo © Danke Galerie

Loop Chairs by Willy Guhl for Eternit (1954)

Photo © Old Exclusives

Loop Chairs by Willy Guhl for Eternit (1954)

Photo © Old Exclusives